# I. How the supply chain allegations unfolded

Boohoo Group (Boohoo) was founded in 2006 in Manchester, England, as an online fashion retailer targeting young consumers globally. By leveraging a direct sourcing model that relies on local suppliers, Boohoo quickly evolved into one of the UK’s most prominent fast fashion houses, and its products were being sold to more than 2.3 million active customers in over 100 countries by the time it began trading on the London Stock Exchange in March 2014. As the company continued to acquire well-known brands over the following years, its market capitalization increased from GBP 560 million (USD 702 million) in March 2014 to GBP 4.5 billion (USD 5.6 billion) by the end of June 2020.

Criticisms against Boohoo started to emerge two years after the company went public. In the 2016 Australian Fashion Report, the organization Baptist World Aid Australia gave the company the worst grade for efforts to mitigate risk of worker exploitation in its supply chains. The following year, a supplier of Boohoo was the subject of an undercover investigation by Channel 4 Dispatches, which found widespread underpayment issues and serious fire risk in the garment industry in Leicester, UK. In 2017, Boohoo was named as one of several UK online retailers selling real fur products mislabeled as faux fur following an investigation by Humane Society International UK and Sky News.

Further allegations arose in 2018 and 2019, including a Financial Times article covering “dark factories” in Leicester, as well as several PETA press releases on Boohoo’s retraction of its pledge to ban wool despite animal cruelty allegations against the wool industry. In January 2019, Boohoo was ranked by the Environmental Audit Committee of the UK Parliament as “least engaged” in its commitments to reduce environmental and social impacts of its products. Five months later, the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers protested Boohoo’s alleged refusal to discuss union representation.

In April 2020, Boohoo reported improved year-on-year sales growth while its competitors’ stores remained closed due to the COVID-19 lockdown. However, the company’s success during the pandemic was set against the backdrop of increasing scrutiny of worker health and safety issues in its supply chain in the UK.

In late March, reports first emerged from local news sources that employees of Boohoo’s Burnley distribution center in Lancashire were forced to continue working, despite physical distancing measures not being established in the facility.

Similar hygiene-related concerns were raised at another distribution center in Tinsley, Sheffield, which serves Boohoo’s subsidiary Pretty Little Thing. Workers at the facilities told The Guardian in early April that orders had increased significantly since Pretty Little Thing started a 70%-off sale.

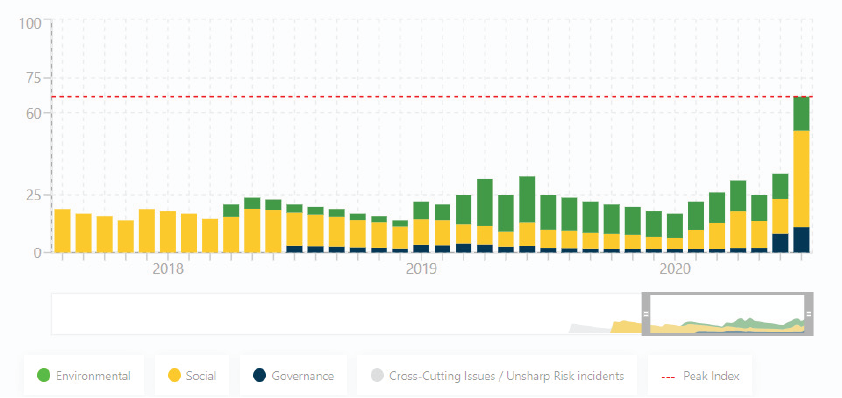

Boohoo’s RRI reaches RepRisk’s high risk category (RRI 67 in July 2020).

On June 30, the NGO Labour Behind the Label published a report detailing poor and unsafe working conditions during the COVID-19 crisis at garment factories in Leicester, a majority of which supply Boohoo and Pretty Little Thing. During the lockdown, the NGO reportedly received reports of furlough fraud, workers being denied pay or forced to work despite being infected with COVID-19, and a lack of protective measures. Some factories allegedly continued to operate illegally during the lockdown due to continuous orders by Boohoo.

The report pointed out that prior to the pandemic, the garment industry in Leicester had faced routine allegations of underpayment and other exploitative labor practices. Labour Behind the Label claimed that these factories employed mostly migrant workers who are vulnerable to abuses, and it was common that they were not able to pay the national minimum wage because of low prices requested by Boohoo.

The story gained further attention on July 5 when Sunday Times reported findings of its undercover investigation at a factory that supplies clothing to Boohoo and one of its brands, Nasty Gal, in Leicester. The undercover reporter found that the factory was reportedly paying its workers GBP 3.5 (USD 4.39) per hour and did not put in place physical distancing measures or provide protective equipment. In response to the report, the UK National Crime Agency confirmed that it was investigating the textile industry in Leicester for modern slavery, and the Home Secretary said the allegations were “truly appalling.”

On July 7 and 8, multiple media reported that retailers such as Amazon, ASOS, Next, and Zalando had removed Boohoo clothing from their online stores, citing concerns over Boohoo’s supply chain practices. Boohoo saw GBP 2 billion (USD 2.5 billion) wiped off its market value.

On July 10, BBC reported that Standard Life Aberdeen, the UK’s largest listed asset manager, was divesting from Boohoo after finding the company’s response to the worker exploitation allegations inadequate.

Were there prior indicators of risk?

RepRisk’s unique research approach and methodology picked up early warning signals on the ESG risks associated with Boohoo. Indicators of risk arose four years before material losses occurred.

The company’s RRI reached RepRisk’s medium risk threshold in 2017 and 2019 when it was linked to allegations of animal mistreatment and poor employment conditions, as well as when its fast fashion business model was under scrutiny for adverse environmental impacts.

Conclusion

The analysis of a company’s ESG risk exposure over time enables stakeholders to take prompt action to mitigate their exposure to such risks. RepRisk analyzes information from public sources and stakeholders on a daily basis. This unique perspective serves as a reality check for how companies conduct their business around the world and to assess whether companies walk their talk.

# II. Boohoo's Supply Chain Code of Conduct

www.boohooplc.com/sustainability/people/supplier-code-of-conduct (last accessed on July 10, 2020) “3.1 The organisation shall provide a safe and hygienic workplace environment bearing in mind the prevailing knowledge of the industry and of any specific hazards.” “5.1 The organisation shall ensure that personnel are compensated according to the law including minimum wage, if applicable overtime premium pay.”

Copyright 2020 RepRisk AG. All rights reserved. RepRisk AG owns all intellectual property rights to this case study. This information herein is given in summary form and does not purport to be complete. Any reference to or distribution of this case study must include the entire case study to provide sufficient context. The information provided in this presentation does not constitute an offer or quote for our services or a recommendation regarding any investment or other business decision. Should you wish to obtain a quote for our services, please contact us.